Building H #73: Can We Teach People to Be Healthy?

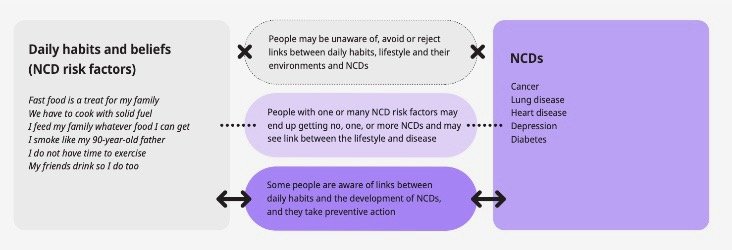

Perhaps the central challenge of public health, and in turn of this Building H project, is to improve the public understanding of how everyday behaviors - our habits, routines, customs, beliefs - manifest into unintended outcomes, those so-called diseases of civilization: obesity, cancer, lung disease, heart disease, depression, diabetes and so on.

This chain of causality creates an existential quandary: How can we convince our fellow human beings that their behaviors will be their undoing? After all, in the context of everyday life, these decisions can seem benign, or perhaps not a conscious choice at all; too many people fall into the default path because they lack the agency or opportunity - the resources, the time, the energy, the understanding - to choose the harder, if healthier, route.

For the past decade or two, we’ve tracked two distinct approaches to help people make healthier choices. First, in the US and other high resource countries, we’ve seen an explosion of digital tools - mobile apps most frequently - to help nudge people (a ping here, a bleep there) to do something differently. We call these nag apps, and we don’t care for them much. Or rather, we don’t think they solve the problem at hand. While they can work well for some people, they don’t really scale to the masses, for all sorts of reasons. Mostly, we think they just miss the mark: these digital tools put the onus on individuals to de-program what the world at large is doing to them. It’s not a fair fight.

But recent years have also seen another, less technical approach to public-health level behavior change: a more basic and potentially more scalable ground-game that seeks to educate people enough to change their behavior, and thus change their outcomes. On a policy level, this effort is typically described as “health literacy” - the effort to help individuals understand and use information that promotes and maintains their own good health, to paraphrase a World Health Organization definition.

For more than a decade, the WHO has advanced health literacy as a cornerstone of its efforts to improve human health. Last month, the agency’s efforts culminated in a reckoning, a massive four-volume, 222-page report titled Health Literacy Development for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases, evaluating how well health literacy efforts, tailored to the needs of specific populations and circumstances, have worked to advance human health. So we dug in to see if health literacy is, in fact, the approach we need to counter-program civilization. (We read four-volume, 222-page WHO reports so you don’t have to!)

The report does an outstanding job of framing health as the inherent, inevitable, invisible consequence of daily life. “People may be unaware of, avoid or reject links between daily habits, lifestyle and their environments and [non-communicable diseases],” the report says, noting that “health choices are often restricted by social and environmental factors beyond the control of individuals.”

Health literacy endeavors to allow individuals to see these invisible factors, and to see their own role in their health. And the more specific a literacy effort is to the cultural context, the more effective it might be. The report provides vivid case studies of health literacy in action: an effort to educate Egyptian fishermen about local health services; workshops in Portugual to help people learn to manage their diabetes; working with diverse communities in Australia to improve breast cancer screening rates; and so on.

Education, of course, has long been correlated with health. Higher education levels dovetail with longer lifespan and better quality of life. The perennial question has been which way does causality go: does education lead to health or do healthier people tend to get better opportunities? (the answer: both). Health literacy is in some ways an attempt to weaponize this correlation, or at least to try to use specific education initiatives to target specific health outcomes.

But for all of its thoroughness, the report falls short in that it acknowledges the so-called social determinants of health - the social settings and social factors that impact health outcomes - but it scarcely acknowledges that these social factors result from commerce, that the commercial products of everyday life have as much influence as the social practices thoroughly documented. It doesn't allow that the determinants themselves could be terminated.

As a commentary in The Lancet points out, “The private sector sets research agendas, shapes narratives, and markets its products in ways that compromise health literacy, not only by misleading individuals, but also by fostering unhealthy communities and societies….Health-care stakeholders have often struggled to amplify their voices over the messages of the private sector.”

The WHO report underscores just how outgunned public health is in this contest, when the full force of daily life pushes the other way, with temptations and obstacles and compromises at every turn. Giving people an understanding of these factors - and some tools to avert their pull - offers another level for health literacy efforts, to instill more agency in our lives, and to remind us all that our culture is the result not just of our individual decisions but of conscious choices by commercial enterprises that are intended to advance their interests, not the public’s.

Read the full newsletter.