Building H #66: Evidence of Healthy Life

At Building H, our very name suggests that we need to, you know, BUILD something to achieve health. But part of our hypothesis has always been that an essential part of a healthy environment is the outdoors - that our time spent in the built environment and the product environment need to be countered with time in nature.

This idea got a massive boost this month with a new paper in Science Advances. The paper, written by a group led by graduate student Lam Huynh from the Graduate Program in Sustainability Science at the University of Tokyo, has the chewy title of “Linking the nonmaterial dimensions of human-nature relations and human well-being through cultural ecosystem services” - not exactly the stuff that invokes pastoral visions of natural splendor. But the wonky title reflects the seriousness of the academic effort here: a quantitative analysis of the impact of the natural world on human well-being, based on a systematic literature review of more than 300 studies from around the globe.

The study uses the concept of “cultural ecosystem services” for its analysis, the notion that alongside the material benefits humans derive from nature - food, water, raw materials - we also enjoy various nonmaterial benefits, such as recreation and tourism. Plenty of research has explored those benefits, but the literature has not been consistent in how they are measured, or in the factors they considered. So there’s been little to no evolving or consensus assessment of the benefits nature provides.

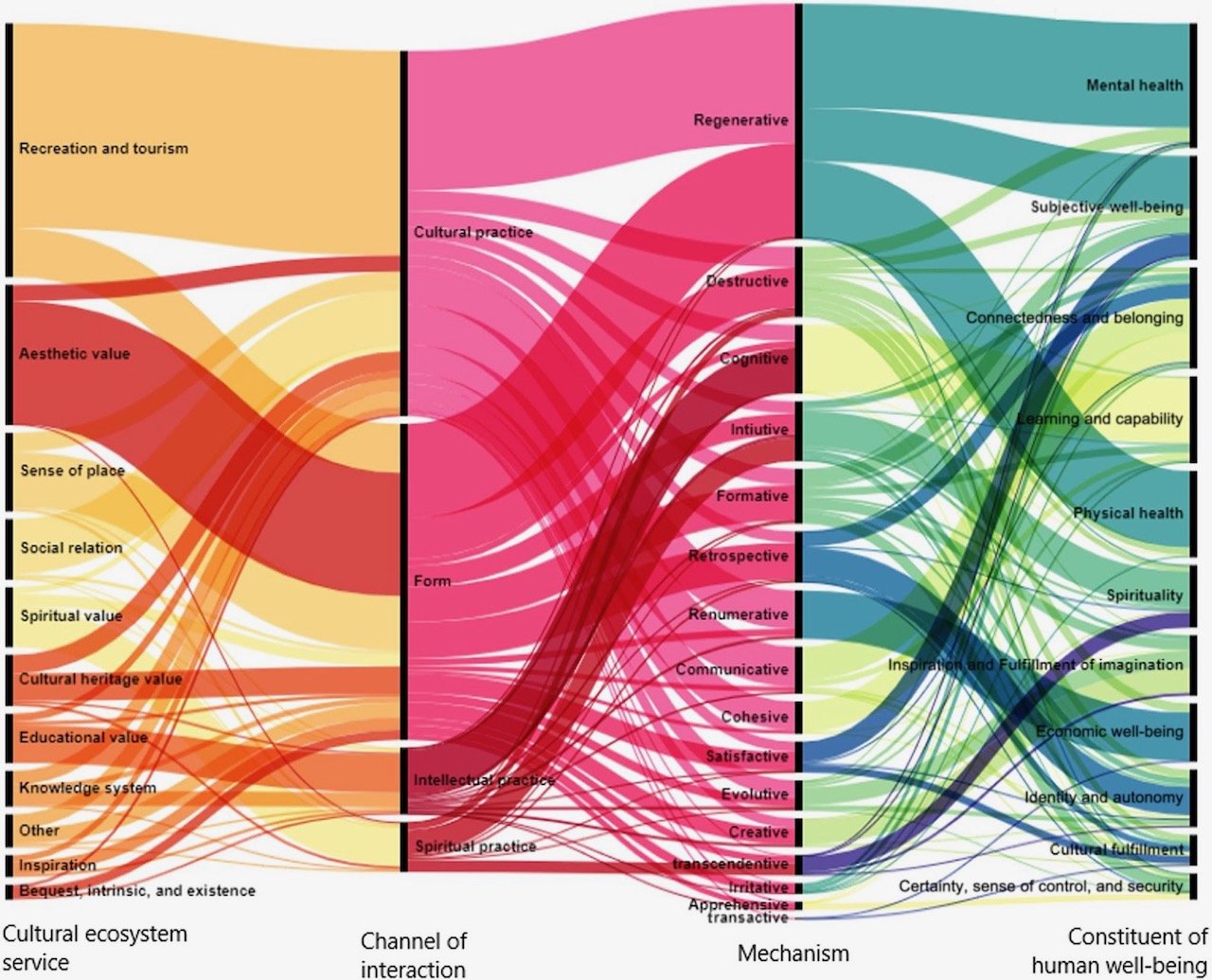

This paper changes all that. By categorizing the literature into 1,134 inputs and 16 categories of outputs, the team was able to synthesize the existing research into a coherent analysis that authoritatively measures the benefits we enjoy from the natural world. (This flow is elegantly shown in the Sankey diagram below - we are suckers for a good Sankey chart.)

If you’ve made it this far, you will appreciate some of the details in the actual paper, such as this section that acknowledges that not all associations with nature are positive. “It is well documented that ecosystem disservices such as noise from wildlife, wild and messy landscapes, and the presence and movement of pests can cause perceptions of disorder, while animal waste and plant litter may cause disgust.” Yuck. Indeed.

But overall, the study shows with data, evidence, and authority that humans derive tremendous and measurable value from the natural world, especially insofar as it affects our mental and physical health.

Of course this in itself is not a new notion. Painters and poets have explored this connection for centuries, conceiving nature as a magical realm of renewal. As William Wordsworth wrote in 1798, in his Tintern Abbey poem, recalling memories of time spent rambling in the Wye Valley:

But oft, in lonely rooms, and 'mid the din

Of towns and cities, I have owed to them,

In hours of weariness, sensations sweet,

Felt in the blood, and felt along the heart;

And passing even into my purer mind

With tranquil restoration

More recently, naturalist E.O. Wilson explored this connection more rigorously in his 1984 book Biophilia. “To explore and affiliate with life is a deep and complicated process in mental development," Wilson writes. "Our existence depends on this propensity, our spirit is woven from it, hope rises on its current.” In this book, and some of his subsequent work, Wilson helped put this natural connection into the realm of science, suggesting that there is an inherent - even genetic - link that conjoins humanity to our natural worlds, despite our modern efforts to wall it off.

Biophilic design is an outgrowth of Wilson’s philosophy, a movement to build nature back into our environments. At its best, biophilic design means more than office plants and water fountains. It’s an architectural movement to make our homes and workplaces more incorporated with natural elements with the express intent of fostering a healthier and more healing experience. In its most ambitious forms, biophilic design creates environments that are invigorating, nurturing, and - as Wordsworth said - restorative. This has been working its way into healthcare, too, such as at the company Parsley Health.

Hopefully, this amazing new paper will provide a boost for such efforts, a quantitative grounding that will foster more people to recognize that nature is not the world out there, but that it is our world, and that it plays an essential role in maintaining human health. Hopefully, it will encourage more biophilic design and building environments that don’t just contain us - they sustain us.

See? It all comes back to Building Health.

Read the full newsletter.