Building H #81: Where the Sidewalk Ends

Last weekend, in three separate incidents in New York City, three people, walking across the street, were struck and killed by cars. They are the latest victims in a horrific national trend of increasing road violence, dating back more than a decade.

In 2021, the latest full year of data available, car drivers struck and killed a record staggering 7,485 Americans walking. (“Pedestrians,” the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration calls these people, but that word - pedestrians - has always bugged us. It’s a stilted, officious term that has no real constituency: a pedestrian, after all, is just a person who happens to be outside, walking.)

That 7,485 was the largest number of fatalities in four decades. And lamentably, it looks likely to be outpaced in 2022, once the full data comes in. Many blame this on the pandemic, but in fact the numbers have been trending worse for more than a decade; indeed, the number of people-killed-by-cars-while-walking has increased more than 54% since 2010.

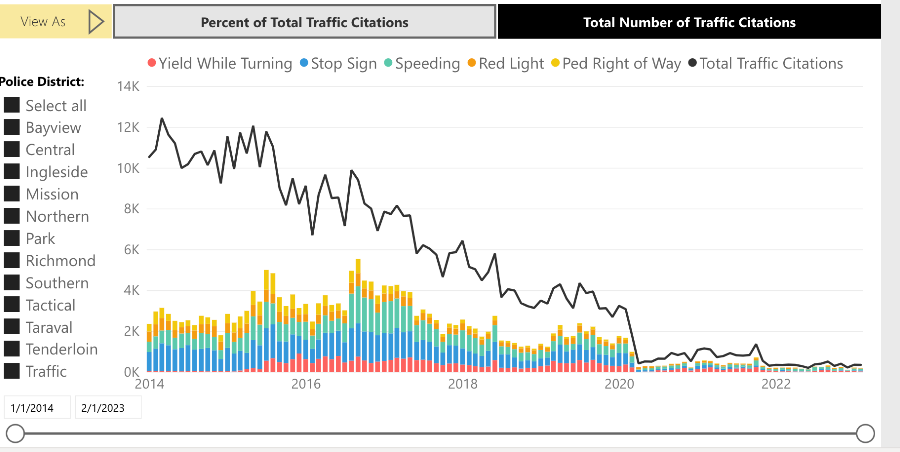

Pedestrian fatalities are just one data point that underscores just how dangerous our streets have become, as drivers feel more emboldened and entitled than ever. Anyone who lives in a US city bears witness on a daily basis to the flagrant speeding and red-light-running and all-around lawlessness on America’s streets. It’s not your imagination: speeding is worse and enforcement has dropped way off. In San Francisco, for instance, citations for traffic violations have almost disappeared in 2023 - as anyone out there can attest. The reasons here are partly local, but also represent a wider perverse tacit acceptance for something that should be patently unacceptable, especially amongst our local leaders and law enforcement. Something has broken in the way people drive today, and enforcement - both police and local government - have not caught up.

What to do? Well, this is, of course, largely a public safety issue that demands policy solutions - again, the province of our local and federal officials who set and enforce the rules of the road. If people don’t have a place to walk, or if they don’t feel safe walking, then it’s understandable that they won’t be inclined to go outside for a stroll.

So why is this a Building H issue? After all, as a rule, Building H is usually focused on private sector interactions and responsibilities. But this is an area where the political is personal. We watch the degradation of public safety everyday, and wonder how we might help fix it. Transportation, after all, is one of the four industries that directly impact public health which we track at Building H. And walking - e.g., getting outside – is a behavior that, in and of itself, is highly correlated with positive health outcomes. We call this behavior “outsiding”, because it’s its own thing. Outsiding is distinct from exercising (which also matters, as a different behavior) - it’s just the very fact of being outside which in most contexts involves, well, walking down a street. But who’s going to venture outside if there’s no place to safely walk down the street? It’s just too dangerous out there. Better to stay inside and watch YouTube.

So how to fix this - who to blame? Well, in many cases, we suspect that dangerous driving is a lot like shoplifting - the worst actors are responsible for most of the problem. In NYC, data showed that fully ⅓ of shoplifting robberies were perpetrated by just 327 people. It’s likely the same for traffic violations: the worst drivers are disproportionately responsible for creating the most danger. Scofflaws who have dozens - or hundreds - of traffic violations but still prowl the streets are often the ones behind the wheel in a fatal accident (when they are caught, that is: a staggering 1 in 4 of pedestrian fatalities is a hit-and-run). And low-income, non-white neighborhoods are disproportionately at a higher risk for dangerous traffic, as many studies have found.

Part of the solution is infrastructure: people need a safe pace to walk, a space which we usually call “sidewalks.” That word itself reflects a bias, of course - “side-walks” suggests that they are adjacent and subordinate to the “main” purpose of a road - the passage of cars. That bias is also, by the way, reflected in how we budget for sidewalks versus roads. A recent ingenious piece of research by economist Peyton Jane Gibson found that American cities spend an average of just 5% on sidewalks compared to the 95% they spend on roads.

In fact, sidewalks are widely recognized as sucky and neglected infrastructure in cities across the US, from Twin Falls, Idaho to Erie, Pennsylvania to Ann Arbor, Michigan. Sidewalks can also be controversial; as recently as 2014 in Edina, Minnesota (a wealthy suburb of Minneapolis), residents opposed new sidewalks based on the fear that people might use them to walk into their neighborhoods. (A new level of NIMBYism - Don’t build it so they hopefully won’t come?)

But it turns out that sidewalks matter even more than we might think, as a clever study led by Quynh Nguyen, professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of Maryland School of Public Health shows (we noted this study in a recent newsletter, btw). Nguyen’s team analyzed 164 million images from Google Street View of urban, suburban and rural roadways across the US. The team trained a computer to spot and label features of the built environment: roads, sidewalks and such. And then they compared the data to demographic and socioeconomic data from the US Census Bureau and CDC.

The team found that walkability indicators such as crosswalks, sidewalks, and stop signs were associated with better health, including reduction in depression, obesity, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol.

(See for yourself: they built a cool mapping tool here. You can also read the full paper and nerd-out with the whole special issue - “Big Data for Public Health Research and Practice” - here).

So yes, sidewalks matter, for safety and for health. But again, given that Building H is focused on how companies can act… how does the private sector factor in here?

One point of leverage is so-called walkability, which emerged in the 1960s (thank you, Jane Jacobs) and it turns out is a factor that matters a lot to real estate and retail businesses. Walkable streets have been shown to directly contribute to higher economic activity (nerd note: while the Department of Transportation suggests a minimum standard of a 6-foot wide sidewalk, Jacobs advocated for a 15, 20, or even a luxurious 30 foot width. Now that is a SIDE-walk!).

This notion of “walkability” was codified and commodified in the early 2000s by Walk Score, a company that is now owned by Redfin, the real estate company. Walk Score creates a 1-to-100 rating for neighborhoods, based on the volume of economic activity and ease of movement. And Walkability matters: a higher Walk Score has been shown to increase property values by thousands of dollars. It’s important to note, though, that the scores have been criticized for reflecting wealth and social disparities, and the Environmental Protection Agency has come out with a non-commercial National Walkability Index. Nonetheless, “walkability” has begun to be used as an meaningful input for investing; Smart Growth America, for instance, uses walkability as one input for advising investors on their smart growth investments.

One last thought: recall that Jane Jacobs’ model walkable environment was Greenwich Village in New York City, that same city, of course, where just last weekend three people died after being struck by cars. They were just walking through their neighborhoods with high walkability scores and along relatively wide sidewalks. Sad to say, but better sidewalks won't solve this problem. But at least they’re a beginning.

Let’s hear from you. Comments are open below.

Read the full newsletter.